How Mount Sinai Unlocked a Student’s Passion for Biomedical Research

“I decided to pursue a PhD in Biomedical Sciences in hopes that I could gain…independence as a researcher, and make contributions to bettering human health,” says Henry Weith.

As he embarked on a career after graduating college, Henry Weith did not initially think about continuing his education beyond a bachelor’s degree. Instead, he focused on finding the right job in industry.

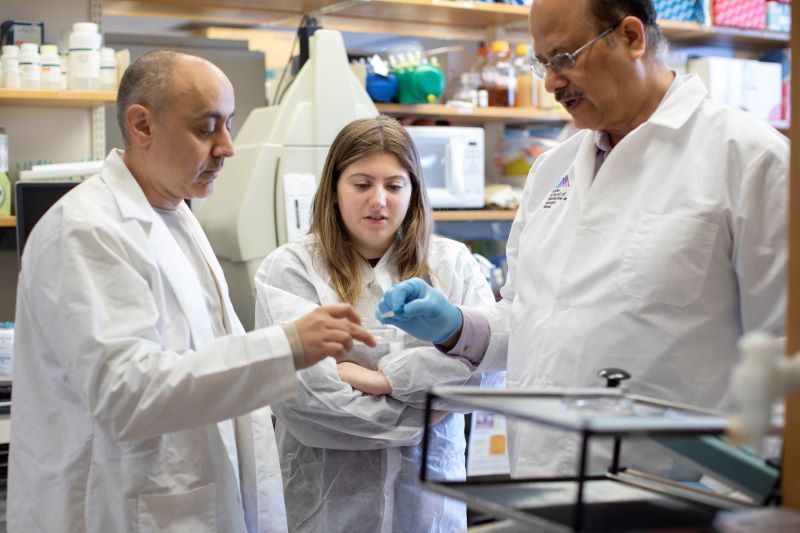

Now a third-year student in the PhD in Biomedical Sciences program at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in the Development, Regeneration, and Stem Cells (DRS) Multidisciplinary Training Area, he works in the laboratory of Alison May, PhD, studying exocrine gland development and preparing for a career that will allow him to address larger scientific areas of inquiry that could eventually improve human health.

“I decided to pursue a PhD in Biomedical Sciences in hopes that I could gain…independence as a researcher, and make contributions to bettering human health,” he says. “Once starting my PhD at Mount Sinai, I found an additional passion for biomedical research that had been hidden under years of tedious, yet essential, courses in cell and molecular biology.”

In this Q&A, he discusses his journey towards a career in biomedical research, and how Mount Sinai is helping him achieve his goals. He explains how learning about what he calls the “innate beauty of developmental biology” demonstrated that unique patterns in nature, something as simple as the scales of a butterfly wing, could be important to understanding the workings of the human body, even something like the human salivary gland. And how working out in the gym is a bit like scientific research in the way hard work is eventually rewarded.

Why continue your education with a PhD in Biomedical Sciences?

Growing up I had never considered continuing my education beyond a bachelor’s degree. Career planning during my undergraduate education was mainly focused on finding a job, which in my major of bioengineering meant an industry position at a biotech company. In subsequent biotech research internships, I recognized that many of the scientists independently directing projects had attained PhDs, which not only gave them more responsibility, but expertise in complex subjects that allowed them to address expansive biological questions that contributed to essential therapies to treat diseases.

What made you interested in the Development, Regeneration, and Stem Cells training area?

One of my first academic research experiences attempted to understand the genomics regulating wing patterning in tropical butterfly species of Central and South America. This experience taught me the innate beauty of developmental biology, not just in the colorful and diverse structures it generates, but also the intricate molecular dynamics that regulate it. Patterning in biology is not just relevant in determining the scales of a butterfly wing but is also crucial to define the body axis of a fly, organize the limb buds of a developing mouse paw, or regulate the branching of a human salivary gland—all of which I believe to be equally beautiful and complex.

Can you give an example in the work in your training area?

In the DRS training area, I’m able to ask fundamental questions and utilize approaches including live cell fluorescent imaging, high throughput transcriptional sequencing, and transgenic animal models to understand how cells are programmed, how they communicate with each other and their environment, and how they appropriately pattern to form healthy tissues. This understanding can then be used to develop regenerative therapies to restore damaged tissues and treat diseases. The faculty of DRS share and enhance this curiosity-driven research through engaging seminars with questions from audience members. In DRS, I’m surrounded by like-minded individuals passionate about teasing apart the basic principles of development and tissue homeostasis.

Why did you choose to study at Mount Sinai?

Mount Sinai offered rigorous research, a welcoming environment, and unbeatable location. I wasn’t certain what specific research I wanted to pursue for my thesis when applying to PhD programs. The number of laboratories at Mount Sinai is extensive and they cover many areas of biomedical science. I was certain I would easily find an interesting research home, which I did following four rotations which made it hard to pick just one. Not only were there lots of exciting and advanced research available, but also the researchers—the current PhD students, post docs, and faculty—were emblematic of an environment that valued collaboration, passion for science, and fulfilling lives outside of research. Everyone I talked to during interviews had a passion outside of research including art, food, athletics, and more. Not only did I feel I’d have adequate work-life balance at Mount Sinai, but its location in New York City meant I could truly make the most of my time outside of the lab, whether it’s running in the park, seeing movies weekly at local theatres, or going out to concerts on the weekend.

What activities outside the classroom have contributed to your success?

Exercise, running or weightlifting outside of lab, has been crucial to maintaining adequate mental health—which I find to be incredibly important for success in research. I know exercise can be very cliché, but what I find most useful about exercise is how hard work is translated to progress in a very straight-forward manner. Biomedical research is full of ups and downs, and sometimes, no matter how hard you try, experiments just don’t work. With exercise, if I run one mile today, tomorrow I’ll likely be able to run 1.25 miles, and if I lift 50 pounds today, tomorrow I may be able to lift 55 pounds. This progress, achieved outside of lab, helps to maintain my self-confidence and assurance that I’m moving forward, even if it doesn’t always feel like my research is.

What are your plans after you complete your PhD?

My current interests align with pursuing a faculty position at an academic research institution where I can split my time between running a lab and teaching. In academia, scientists can have control over their research and the questions they are driven to explore. I value being able to explore scientific phenomena based on curiosity and current health needs outside of the pressure of making profit. Additionally, I’ve enjoyed the experience of mentoring student trainees in lab. After working as a teaching assistant for the Development and Regeneration section of the first-year Biomedical Sciences core course, I want to continue educating budding scientists.

Any thoughts about future research projects?

I’ve enjoyed conducting basic biology research on epithelial development but would love to expand to different organ systems and cell types as well as other model organisms. I plan on pursuing a post-doctoral fellowship immediately following my PhD in hopes of gaining more independence as a research scientist and expanding my expertise to a wider breadth of research topics.