Stories Behind the Science: Preparing to Fight the Next Epidemic

Stories Behind the Science: Preparing to Fight the Next Epidemic

Kris White, PhD, Assistant Professor of Microbiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (right), and lab member Isidora Suazo, PhD, Postdoctoral Fellow (left), are part of a research network to discover new drugs for a viral epidemic preparedness initiative.

It was June 2022, and Peter White, a lawyer from Point Lookout, Long Island, was in Florida attending a work event. As he was waiting for his flight home, he started to feel sick.

“By the time I landed, I was very sick with a heavy pressure in my chest,” said Mr. White, 67. “Any time I had previously felt like this, it had always, at a minimum, developed into bronchitis or pneumonia.”

Mr. White was worried it was COVID-19, which could spell poor outcomes given his underlying respiratory condition. “When I get a cold, it has a tendency to morph into bronchitis and, at times, pneumonia. I’ve had walking pneumonia several times, as well as regular pneumonia,” he said. “I can’t count the number of times I have had bronchitis.”

His doctor advised him to go to the emergency room to seek treatment for COVID-19. Thankfully, just months prior—in December 2021—the antiviral medication Paxlovid (nirmatrelvir/ritonavir) from Pfizer had become available via emergency use authorization for the treatment of COVID-19.

“I did not feel better right away,” Mr. White recalled. “However, I did not get worse, which was huge given my prior history, and it was a comfort for me that the drug was working.”

“Thankfully, his bout with COVID-19 ended up being uneventful, because he was able to take Paxlovid quickly and clear it out of his system,” said Kris White, PhD, Assistant Professor of Microbiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Mr. White’s son.

“The COVID-19 pandemic really taught us the value of having treatments ready to test and deploy quickly when an epidemic hits,” said Dr. White.

Mount Sinai has been working toward that goal, in part through its involvement in the Antiviral Drug Discovery (AViDD) Centers for Pathogens of Pandemic Concern, established in 2022 by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. White’s lab is among several at Mount Sinai contributing research as part of the AViDD Centers, developing antiviral drugs to tackle future outbreaks.

Dr. White (second from right) with his father, Peter (second from left), with five of Dr. White’s children and two nieces. Peter caught COVID-19 in 2022, but with Paxlovid antiviral treatment, it did not develop into something severe, for which Mr. White was at high risk.

However, recent cuts to NIH funding have threatened to stall progress. “We were halfway to the finishing point,” said Dr. White. “With our funding cut, it is like we have half a drug—and that is of no good to anyone.”

Read about how antiviral research can help us navigate future epidemics, and challenges the AViDD Centers face.

‘It Could Have

Been A Very

Different Pandemic’

The issue with relying solely on pharmaceutical companies to develop drugs for an epidemic is that until the health crisis is at hand, there is no incentive for them to carry out such research, noted Dr. White.

That was the case with COVID-19—when it hit in early 2020, there were few if any drug candidates to test right away. Pharmaceutical companies and academic institutions scrambled to find new compounds, or repurpose old ones, that could treat the infection.

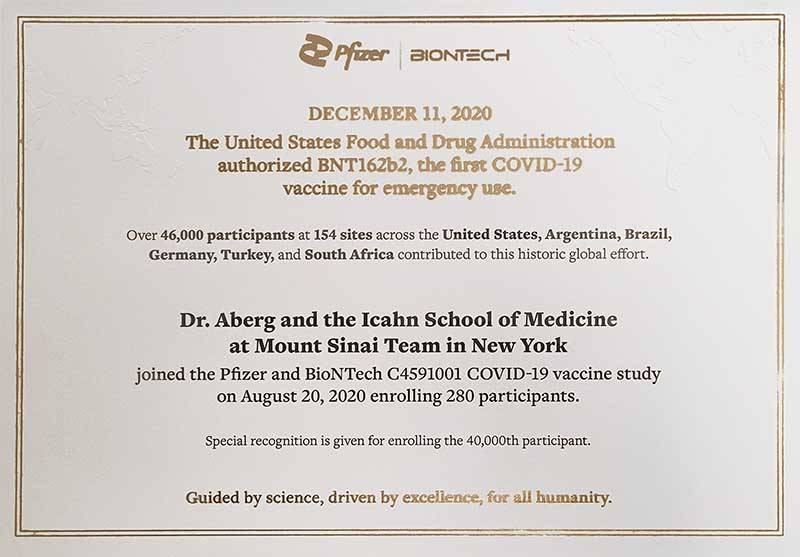

Pfizer had a lead, PF-07321332, which had potential for targeting SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. It was developed in 2003 to address the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2002-2004. But before it could make it into human clinical trials, the outbreak was contained and development was discontinued.

Even promising compounds take time before they can be used on patients. It wasn’t until March 2021 that Pfizer announced it would test PF-07321332 in humans in a phase 1 trial. In June that year, a phase 2/3 trial was carried out to test its effectiveness, and in December, the compound, which had been named Paxlovid, received its emergency-use authorization.

“We’ve seen that given the will, we can quickly test the effectiveness and safety of treatments and make them available to the public,” said Dr. White. “Imagine if we had compounds ready to test right at the beginning, it could have been a very different pandemic.”

For Dr. White’s father, that difference was between life and death. “Paxlovid was a game changer for me,” said Mr. White. “Knowing that I was most likely going to suffer, but not die, from COVID-19 was good news. It would have been better if this drug was available sooner rather than later.”

Having treatments available early on not only reduces transmission, disease severity, and mortality rates, but also has an impact on health policy.

“Having such an antiviral could even have mitigated the need for severe lockdowns, or even vaccine mandates,” said Dr. White. For people who might be ineligible for vaccines, or were resistant to such mandates, having a treatment available would have provided options for health providers and policymakers, he explained.

Kickstarting the Process

Dr. White, seen dressed in protective clothing, works with Biosafety Level 2 and Biosafety Level 3 viruses as part of his work. His lab’s research includes drug discovery of new antivirals and building up animal models of viral infection.

Following the authorization of Paxlovid, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the NIH, realized the benefits of having promising drug candidates ready to be tested at the onset of an outbreak.

“Academic institutions like Mount Sinai were perfectly suited for kickstarting that discovery work,” said Dr. White, whose lab studies viral-host interactions, develops cell culture and animal models of viral infection, and performs other antiviral drug discovery work.

Members of Dr. White’s lab, from left to right: Briana McGovern, BS, Senior Research Associate; Meg Gordon, BA, Research Associate; Dr. White; Dr. Suazo; Jared Benjamin, MS, Research Associate.

“Historically, drug discovery was a process that took billions of dollars, and was usually undertaken by pharmaceutical companies,” said Dr. White. “Now, with technological advances and artificial intelligence, the cost of that process has been brought down to millions of dollars, which is a realm that the federal government can provide funding for.”

NIAID awarded a total of $577 million in 2022 toward the creation of nine AViDD Centers, which collectively work to discover better treatments for SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses, as well as six other pathogen families of concern, which include Ebola, Zika, and other cold-causing viruses. Mount Sinai researchers received a total of $16 million and are involved in four of the nine centers.

Progress

Cut Short

Dr. White handling cell cultures stored in a cold storage unit in his lab.

The AViDD Centers were conceived as a five-year project. However, in March 2025—three years into the Centers’ inception—the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention canceled more than $11 billion in funding earmarked for pandemic response.

This included funding for the AViDD Centers, where researchers had the remainder of their unspent budget terminated immediately, pulling out the rug from under several projects.

“I’ve had to let people go from my lab, and we’re currently working in an unfunded state for the AViDD project,” said Dr. White. “We’re only continuing because we had prepaid for certain things before the funding cutoff.”

The most advanced drug developed thus far was basically a better Paxlovid for targeting coronaviruses, but without the need for the ritonavir component, said Dr. White. This is critical because the ritonavir component severely limits the use of Paxlovid in some patients due to drug interactions with other drugs. That compound is more or less ready for a pharmaceutical company to take over for clinical trial testing, with its patents remaining open access, as directed by the NIH.

“We have an excellent coronavirus drug ready to go to clinical trials, but every other drug for the other viruses—paramyxovirus, filovirus, flavivirus, and more—none of them are even close,” he said.

At best, work on the other viruses are close to getting their animal model efficacy data, which is crucial for moving the drugs into human models, said Dr. White. “Getting animal model data is hard enough in five years. Without funding for the remaining two years, getting that data in just three years is almost impossible.”

Operating costs for AViDD projects are on a larger scale because they involve high-throughput structural biology and biochemistry that run millions of dollars per year, noted Dr. White. Researchers are reaching out for patchwork funding to keep operations going, including from the Department of Defense, NIH, not-for-profit organizations such as the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative, and philanthropy.

Getting continued funding is crucial because viral outbreaks do not take breaks.

“At our labs, we’ve been focusing on Zika virus disease and dengue fever, and these are viral infections we’ve already seen on our shores but still have no treatments for,” said Dr. White.

“At the end of the day, I want to be able to keep my dad and many other people like him safe when—and not if—the next viral outbreak occurs,” said Dr. White. “We were already caught by surprise once with COVID-19. Let’s not have history repeat itself again.”